| ||

| Home | Login | Schedule | Pilot Store | 7-Day IFR | IFR Adventure | Trip Reports | Blog | Fun | Reviews | Weather | Articles | Links | Helicopter | Download | Bio | ||

Site MapSubscribePrivate Pilot Learn to Fly Instrument Pilot 7 day IFR Rating IFR Adventure Commercial Pilot Multi-Engine Pilot Human Factors/CRM Recurrent Training Ground Schools Articles Privacy Policy About Me Keyword:  |

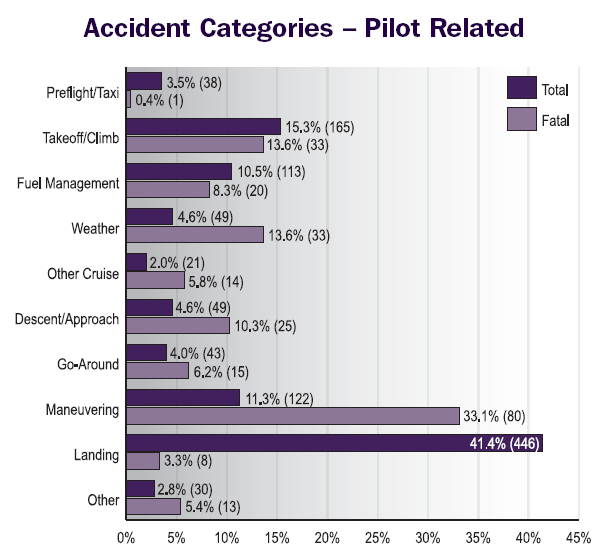

Could you immediately apply the correct control input to recover from a spin? MANEUVERING FLIGHT Maneuvering flight continues to be one of the leading causes of fatal accidents in general aviation. Only 11% of total accidents involve maneuvering flight, but this category of flight represents a full 33% of fatalities. Do we have your attention now?  Before we can act to

prevent these types of accidents, we must

understand what is meant by “maneuvering” flight. The Air Safety

Foundation defines this as including aerobatics, the low pass, buzzing,

pull-up maneuvers, aerial application maneuvers, turns to reverse

direction, or when a pilot attempts to return to the airport when an

engine fails after take (see safety briefing on Heads Up Flight Desk to

the right). Before we can act to

prevent these types of accidents, we must

understand what is meant by “maneuvering” flight. The Air Safety

Foundation defines this as including aerobatics, the low pass, buzzing,

pull-up maneuvers, aerial application maneuvers, turns to reverse

direction, or when a pilot attempts to return to the airport when an

engine fails after take (see safety briefing on Heads Up Flight Desk to

the right).According to the 2006 Nall Report (AOPA Air Safety Foundation), there are three primary reasons for fatal maneuvering accidents. Collision with the ground, trees and wires accounted for 45% of these accidents. Loss of control accounted for 41%, and performing aerobatic maneuvers accounted for another 13%. See graph below. These accidents are very much preventable, simply by using good judgment and decision making. While it may be tempting to buzz your friends house with an aircraft full of buddies, it is a very dangerous realm of flight that you would be putting them (and yourself) into. An airplane at full gross weight handles much differently from one that is lightly loaded. This, combined with either sharp pull-ups from a dive, or steep bank angles, can put you into an accelerated stall. If you are close to the ground, this could be unrecoverable. STALLS A stall can occur at any speed and at any angle of bank. The only thing that is necessary is for the wing to exceed the critical angle of attack. Beyond this angle, the wing stops creating lift. Understanding when to expect this to occur is critical (no pun intended). As your POH clearly shows, weight has a factor in when the wing will stall in level flight. The more weight, the higher the stall speed. When you bank the aircraft and/or pull up sharply, you will feel G-forces. These G-forces have the effect of increasing the weight the wings must lift. Increase these forces to a certain point and you will exceed the critical angle of attack, and you will have an accelerated stall. SPINS If you fail to recognize the stall entry, and happen to be in uncoordinated flight, you are perfectly situated to enter a spin. If you have trained on spins recently, you will have developed a level of “natural reaction” to this situation, and may be able to make the proper control inputs in time for recovery. Spin recovery at low altitude requires immediate and correct control input. This requires a trained response. Spins can only occur when one wing is more stalled than the other. This is one of the reasons your flight instructor kept reminding you to “check the ball”. Most flight instructors prefer not to spin when near the ground! One phase of flight that produces spin accidents all to frequently is the turn to final approach. When a pilot gets distracted and overshoots final, the tendency is to bank steeply to make the turn back to final. At low speeds this creates an overbanking tendency and both the nose and the low wing start to drop. Pilots then attempt to correct for this with opposing rudder, and now we have the perfect recipe for a low altitude spin. Once of the best preventative measures for this scenario is to never exceed a bank of 30 degrees in the pattern, and to accept the flight path that results. Never get steep when you are low and slow.  STALL & SPIN

RECOVERY STALL & SPIN

RECOVERYTo recover from a stall you need to immediately release any rearward yoke (or stick) pressure, and push forward enough to reduce the angle of attack. This will allow air to flow over the wing at an angle less than the critical angle, and you are flying again. Right after reducing the angle of attack, apply power in order to maintain flying speed. Spin recovery requires immediate reduction of power to idle, application of full opposite rudder (opposite to direction of spin), followed by moving the yoke forward far enough to reduce the angle of attack to below the critical angle. Once the spin has stopped, you will be very nose low, so you should carefully pull the yoke to the rear to stop the resulting dive. Once you are in level flight, you should add power as needed to maintain your desired speed. RECOMMENDATION If you haven’t trained in spin or unusual attitude recovery, your instinctive response just won’t be there if you ever needed it. Find a qualified flight instructor, and an airplane certified for spins, and go try a few actual spin and unusual attitude recoveries. You may botch a few recoveries in practice, but you will learn the correct response, so you don’t botch the recovery if you ever really need it. Your Thoughts... |

|

| Home | Login | Schedule | Pilot Store | 7-Day IFR | IFR Adventure | Trip Reports | Blog | Fun | Reviews | Weather | Articles | Links | Helicopter | Download | Bio |

| All content is Copyright 2002-2010 by Darren Smith. All rights reserved. Subject to change without notice. This website is not a substitute for competent flight instruction. There are no representations or warranties of any kind made pertaining to this service/information and any warranty, express or implied, is excluded and disclaimed including but not limited to the implied warranties of merchantability and/or fitness for a particular purpose. Under no circumstances or theories of liability, including without limitation the negligence of any party, contract, warranty or strict liability in tort, shall the website creator/author or any of its affiliated or related organizations be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, consequential or punitive damages as a result of the use of, or the inability to use, any information provided through this service even if advised of the possibility of such damages. For more information about this website, including the privacy policy, see about this website. |